This essay was written about my experiences as a cisgender female, AFAB person, so most of the language directly refers to those identities. However, this essay is for anyone who menstruates, has a uterus, or absorbed cultural ideals of femininity. I hope my experiences resonate.

This essay was written about my experiences as a cisgender female, AFAB person, so most of the language directly refers to those identities. However, this essay is for anyone who menstruates, has a uterus, or absorbed cultural ideals of femininity. I hope my experiences resonate.

I got my first period in seventh grade. It was Thanksgiving weekend, and for whatever reason (sometimes the universe doth giveth), my family was skipping the festivities and staying home that year. During my morning pee, I noticed my underwear was brown. I didn’t know why I’d pooped my pants for the first time post-potty-training, but I shrugged it off and continued on with everyone’s favorite colonizer holiday. Every time I went to the bathroom that day, the brown stains returned. I changed three times before I solicited my Mom’s help. That’s when she unceremoniously informed me I had been inducted into womanhood: She handed me a pad and the rest is herstory. Neither of us explained to my Dad why I was crying into my mashed potatoes at dinner that evening. My period was a personal burden to be kept hidden.

Until freshman year, when I got my period at school and didn’t have any “ladies’ accessories.” I approached the nicest girl in my English class and whisper-asked her, “Do you have a tampon?” Before she could respond, an eavesdropping boy shouted at the top of his lungs, “EWW! THAT’S DISGUSTING.” In that moment, and a million other ones like it, my relationship with my body became abrasive. My body and her natural cycles had been deemed obscene, offensive, and wrong.

My relationship status with my monthly cycle continued to be “It’s Complicated” until about a decade-ish later when I stopped getting it. After years of desperately trying to shrink my body with little food and lots of exercise, my uterus finally decided it didn’t have the skills to keep up in this fast-paced environment. Just kidding! Actually, I was depriving her of nutrients until she finally determined I must be in perpetual famine, and creating a new life wasn’t a priority. Losing my period was the catalyst I needed to seek help: I never thought much about motherhood until I was confronted with the possibility of losing it.

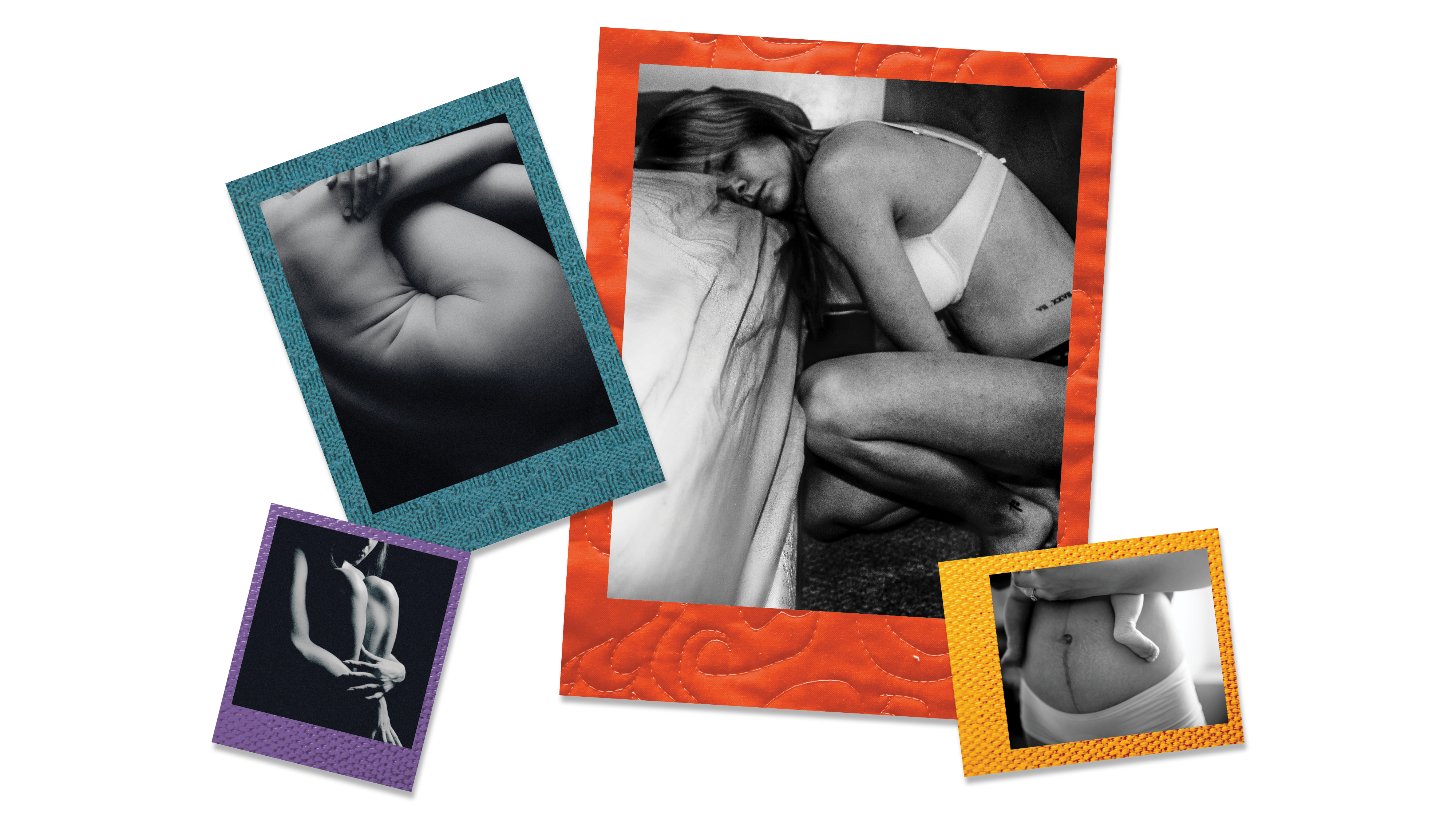

After a lifetime of being told that girls don’t poop, don’t have thighs that kiss in the middle, and don’t talk openly about their bodily functions, my body-ody-ody and I were far from besties. (Thee Stallion, Megan 2022). Amenorrhea, which is doctor-speak for “no periods”, flipped my “frenemy” status with my body upside down. To get back into natural rhythms, I had to really love on her after years of waging war. I ate plenty of nourishing food, moved in gentle ways, and got an abundance of rest. In a society that teaches femme people to control, hate, and punish their bodies, that kind of tender love and care is antithetical to everything we are told about being and becoming women.

Female socialization includes a constant barrage of conflicting messages which we all absorb like extra-super tampons. We are shamed for having periods, but our value is interwoven into motherhood. Our social capital is determined by our physical attractiveness, but we are judged harshly for capitalizing on our sexuality. We are congratulated for staying small but chastised for being too small. Most importantly, women’s bodies are for controlling. Heaven forbid women smell, burp, fart, or have hair below our eyebrows. We are discouraged from bleeding freely and openly, as nature intended. Essentially, we are told ideal womanhood is achieved by becoming blow-up sex dolls with ovens ripe for procreation. Legally, politicians argue we have fewer rights to our bodily autonomy than a clump of cells. The content of our uteruses is considered more important than our lives or livelihood. Is it a surprise that lots of women end up in antagonistic relationships with their bodies?

Nearly the length of two typical human gestations ago (June 2022), the U.S. Supreme Court overturned one of the most publicly contested and important cases in our country’s history, Roe v. Wade, ending the legal right to abortion that has been upheld for decades. Since then, access to lifesaving and vital reproductive healthcare has been rolled back in over half of U.S. states to varying degrees. The quality of maternity care in those states has plummeted, with many doctors fleeing to blue states or losing the ability to legally provide their patients with necessary life-saving medicine. Over and over again, research shows that criminalizing abortion doesn’t prevent or stop it from happening, but it does increase the likelihood of negative outcomes for people with uteruses.

Motherhood (and parenthood in general) is a really big choice. Manufacturing, nourishing, and pushing out a new little human is accompanied by a lot of potential consequences. As miraculous as it is, choosing motherhood means willingly giving up your bodily autonomy to a little alien who will suck all the life out of you. (Or so I’ve heard.) I’ve never done it before, but childbirth sounds like an emotional rollercoaster of beauty, pain, exhilaration, and gore. You can literally rip a gaping hole between your legs like I did to my mother, which she kindly reminds me of every so often. (I’ve always been one to make a dramatic entrance.) Incidentally, it’s pretty incredible that millions of women choose to make that sacrifice anyway.

Motherhood can be a burden, but it can also be a gift. What an enchanted fairytale it is that bodies can create a new life from basically nothing. I’m not the first person to write about reproductive rights, and I certainly won’t be the last, so I’ll spare you the usual arguments. What I’m curious about is how the abortion debate penetrates our relationships with our bodies, coupled with all the other twisted cultural messages women receive. What exactly are we telling femme people about their bodies and their inherent value when we take their choices about their bodies away from them?

As I sit here writing this essay, I have my period. These days, when the blood returns between my legs, I greet her like an old friend. My menstrual cycle serves as a joyous celebration of all the incredible magic my body can do, like run 13.1 miles, teach back-to-back yoga classes, fill sketchbooks with art, and (maybe) create a new life. She reminds me of how hard I worked to earn a loving relationship with myself. I think I want to be a mom someday, but I have a lot of other things to do first.

We often neglect to discuss that being pro-choice means making space for choosing motherhood, too, when the timing is right. Feminism is about making space for options and returning people’s autonomy to them.

When people have agency over their bodies and their lives, we all collectively benefit. Similarly, women bravely declaring their bodily functions, defying societal expectations, protesting the government’s attempts to infringe upon their bodily autonomy, and choosing whether or not they want to be mothers are all radical ways we can love on our bodies, despite the messages we receive to the contrary.

Finally — If I could get in a 1985 Delorean and speed back to that high school English classroom in 2007, I would say, “Fuck off, Brad! I am a fertile goddess, and your body can’t do half the things that my body can.” More than anything, though, I wish I could go back and love her then like I love her now.